What can weather history teach us? Quite a bit if you talk to Sarah Jamison, a Cleveland, Ohio, based hydrologist with the National Weather Service. Sarah’s what I call a “weather storyteller” — she’s the expert I sought out while researching the strange meteorological events that led to the1913 Dayton flood – a key setting for my up-and-coming historical novel, Torrential.

“The Weather Bureau offices for Indiana and Ohio on the morning of March 24, 1913 were calling for ‘unsettled weather, with rain or snow that night and colder Tuesday,’” Sarah said, referencing historical records during our background interview for my novel.

Of course, what happened over the next 24 hours has gone down in National Weather Service history: a combination of two high-pressure systems created a stream of moisture from the Gulf of Mexico that stalled right over the Ohio Valley, leading to intense rainfall – the equivalent of six months of runoff in two days. Some nine to 11 inches of rain fell that Easter weekend on ground already saturated from an early spring thaw. The torrent proved too much for the city’s levees, which broke early on the morning of March 25, and catapulted the city under up to 24 feet of water in places. The disaster cost Dayton more than 360 lives, and property losses of $100 million, or more than $2 billion in today’s dollars.

The flood that laid waste to Dayton wasn’t the end of Ohio’s weather woes. In November of that year, the Great Lakes were struck by a massive storm system combining whiteout blizzard conditions and hurricane force winds. The centennial of the storm, known as the “White Hurricane of 1913,” is this Saturday. It lasted for four days, during which the region endured 90-mile per hour winds and waves reaching 35 feet in height.

“The Ohio Valley experienced its most destructive year on record due to the floods in March and the storms in November of 1913,” says Sarah. “When I researched the large-scale weather patterns that existed around the time of these storms, there was nothing particularly uncommon about them. In these instances the weather conditions just happened to coincide in such a way to produce these unprecedented storms. What this tells me is that we will be vulnerable for such storms in the future.”

She’s often called to document details of past storms for anniversaries – her first such project was the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Floyd that devastated North Carolina. We crossed paths when she worked on the Dayton flood centennial (see blog post marking this event).

Sarah’s passion for informing the public of historical weather disasters serves many purposes, most significantly, “retelling the stories of these historic disasters helps remind people of their vulnerabilities,” says the Florida Institute of Technology meteorology graduate.

“In my profession we are fairly familiar with the historic weather disasters that shape our regional history. But is the public? Unfortunately, after recent disasters we hear the all-too-familiar statement from those directly impacted, ‘I never thought this could happen.’ Didn’t they know that the flood of 1913 had water 10 feet higher than this flood? How did they not know they were in a flood plain? Educating the public on their regional weather history can play an important role in preserving life and property in the future.”

Sarah began her National Weather Service career in Portland, Maine, in 2002. She has since worked at the forecast offices in Kansas City and the Outer Banks of North Carolina before being based in Cleveland in 2010.

She notes that weather “has played a critical role in historic events, from the Normandy Invasion to the crossing on the Delaware.”

Sarah, along with her colleagues in climatology, concur that we are experiencing more extreme weather disasters from floods to droughts to hurricanes and tornadoes (The Writing Well previously addressed the topic of extreme weather when it featured award-winning science journalist Linda Marsa, author of Fevered).

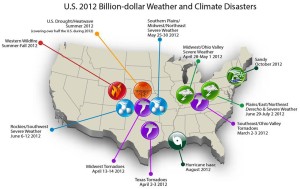

In 2012, weather and climate disasters cost the U.S. $110 billion, with Hurricane Sandy alone causing damages of $65 billion, NOAA reported.

“From a hydrologist perspective, the threat of more extreme droughts and floods is very worrisome,” she says. “If the same area (of Dayton, Ohio) was to be impacted by the rains of March 1913 today, we would see far more reaching impacts than we did in 1913.”

She attributes that to the growth in communities in flood plains. “Fortunately, forward-thinking individuals in Ohio made great strides in flood mitigation after the flood of 1913, so some of the more severe impacts would be lessened, especially in the Muskingum and Miami River watersheds. The biggest victory we could take away from a similar storm would be the great reduction in loss of life as forecasts now provide days of advance notice of storms of this magnitude.”

Often in these storms, loss of life is due to people not recognizing that they are in a life-threatening situation. Sarah and her National Weather Service colleagues are now collaborating more closely with public and private agencies to promote public safety and preparedness in the face of devastating storms. The group, Silver Jackets, was launched during the centennial of the Great Dayton Flood. It leverages the resources and manpower of dozens of agencies.

Often in these storms, loss of life is due to people not recognizing that they are in a life-threatening situation. Sarah and her National Weather Service colleagues are now collaborating more closely with public and private agencies to promote public safety and preparedness in the face of devastating storms. The group, Silver Jackets, was launched during the centennial of the Great Dayton Flood. It leverages the resources and manpower of dozens of agencies.

As I watch news headlines of the impending land fall of Super Typhoon Haiyan, predicted by some to be the largest storm ever recorded, over the Philippine Islands, I can’t help being thankful that the US is marshaling its resources to build a more coordinated early-warning platform here.

As for Sarah, she’s already looking ahead to the next opportunity to educate the public. NOAA and the National Weather Service are sponsoring “Storms of the Great Lakes” exhibit at the Great Lakes Science Center on the Cleveland waterfront mainly to pay tribute to the “White Hurricane” of 1913. Sarah also is gearing up for the anniversary of Hurricane Hazel. Unfortunately (or fortunately) for this history-minded hydrologist, there are no shortage of regions in the country from which to find weather disasters.

“I encourage those in my field and supporting agencies like those in the Silver Jackets to take advantage of these opportunities to bring these storms back to life.”

Concluding our interview, Sarah leaves me with a fitting quote form one of her favorite historical figures – Winston Churchill, whose name she bestowed on her cat:

“When the situation was manageable it was neglected, and now that it is thoroughly out of hand we apply too late the remedies which then might have effected a cure. There is nothing new in the story. It is as old as the sibylline books. It falls into that long, dismal catalogue of the fruitlessness of experience and the confirmed unteachability of mankind. Want of foresight, unwillingness to act when action would be simple and effective, lack of clear thinking, confusion of counsel until the emergency comes, until self-preservation strikes its jarring gong–these are the features which constitute the endless repetition of history.”

—House of Commons, 2 May 1935