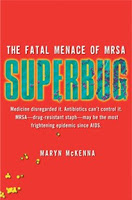

My blog is normally devoted to talking about communications trends, writing tips, etc. When I headed to Danya International yesterday, a government contractor that works with CDC on health communications and program evaluation activities, to hear about Maryn McKenna’s new book SUPERBUG: The Fatal Menace of MRSA, about the growing epidemic of drug-resistant staph, I fully expected to leave with insights into this frightening epidemic, and into the writing path that got McKenna to this book.

Afterall, she was an award-winning health reporter at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, who got her nickname “Scary Disease Girl” during her tenure covering CDC and the government’s investigations of major disease outbreaks.

Afterall, she was an award-winning health reporter at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, who got her nickname “Scary Disease Girl” during her tenure covering CDC and the government’s investigations of major disease outbreaks.I was completely blown away by what I learned about MRSA and the lack of a coordinated response to this spreading crisis by the medical community here in theU.S. I suppose it shouldn’t be that big of a surprise, given that it’s an industry that polices itself.

First, some facts:

- One-third of theU.S. population walks around all the time with MRSA on their skin and in their noses. It’s a very common bacterial found on large numbers of people.

- In theU.S. in a single year, there are 19,000 deaths and 370,000 hospitalizations from MRSA. Overall healthcare spending on combating it is conservatively estimated at $4.8 billion a year.

- In 1968, it arrived in theU.S. strictly as a “hospital infection” targeting mostly the elderly.

- In 1980, it struck a hospital in WashingtonState, when a car accident victim in Texas was transported to Seattle and passed the skin infection on in the burn unit and later the ICU.

- Community-based strains of MRSA are affecting kids – specifically, student athletes as the news headlines continue to report. The kids are not showering and are not cleaning their sports equipment. They are getting it from skin-to-skin contact.

One Mother’s Nightmare

But MRSA also has infected healthy women after they give birth in hospitals. Women like Diane Lore, a 20-year journalist and former medical editor of the AJC, who is featured in McKenna’s book. She contracted a community-based strain of MRSA in June 2003 after giving birth to her third child, when her baby daughter first clamped down so hard that she tore her mo ther’s right nipple.

Family video footage inside the hospital room before the breastfeeding occurred showed a gloved nurse inserting a finger into the child’s mouth to calm the crying baby. Lore, who lost six months of bonding time with her infant daughter combating the infection, eventually overcame it after enduring incorrect diagnoses, and multiple courses of antibiotics until she finally received the right treatment. Not surprisingly, she and her husband also faced a formidable battle with their insurance company on covering the expensive treatment. Lore held up a bottle of some of the leftover course of antibiotics, which she held onto even after her bout with MRSA passed out of fear of a return of the infection. The cost of one little white pill was a staggering $100.

“It was a horrible, traumatic time,” Lore said, “I don’t’ remember my little girl at all. I was quarantined up in my son’s bedroom (out of fear that she was infectious.)” At one point, she and her husband drew up their will and had their “last talks.”

“MRSA was a hospital infection but it’s not – it was just MRSA’s first epidemic,” notes McKenna, explaining that contingents within the medical establishment were very reluctant to acknowledge that community-based strains could actually hit inside a hospital.

The third wave of the epidemic is now cropping up in ano ther area — agriculture – infecting both farmers and their animals, notably pigs, which means it will find its way into the food chain. The culprit? Widespread use of antibiotics and the overcrowded living conditions of the animals on industrialized farms.

What We Can Do

So, what can be done about preventing MRSA’s spread?

Hygiene is king — McKenna urges everyone to wash their hands frequently. If you are going to the hospital or have a loved one going in, get screened for MRSA first. People entering ERs should be screened before being admitted into the general hospital population. This practice of isolation and detection is widely used in parts of Europe and a CDC trial of a Veteran’s Hospital in Pittsburgh was so effective that it’s now in full force in all hospitals in the VA system, McKenna says.

And, hospital staff needs to be educated on hygiene practices, including frequent hand washings and glove changes. “Non-stop messaging” and the threat of lost executive bonuses helped one Charlotte, N.C., hospital get hand-washing hygiene up to 98 percent from 50 percent.

McKenna holds out hope that the move toward electronic healthcare records, which would enable “people’s records to be portable with them,” could help doctors more quickly diagnose MRSA in patients. Also, new rapid test equipment, currently very expensive, can detect MRSA within 24 hours. She also urges people to not be afraid to ask questions of doctors and nurses. Lore urges that if you have a loved one sick in the hospital, be a watchdog and advocate by their bedside.

Word of Mouth

Mike Greenwell, Danya’s vice president of Health Marketing and Communications, notes that Danya will be assisting CDC with a public service campaign on MRSA in the coming months, and he sought input on whether the campaign should target healthcare workers or consumers. The consensus was the general public.On the communications front, word of mouth through social media and leveraging mommy bloggers are important outreach methods, which are going to be relied on more given the cutbacks in investigative, in-depth health reporting in newspaper rooms around the country.

So, stay tuned, you will be hearing more about MRSA’ s menace and what we as a society need to do to combat its spread. And keep your hands clean.

Listen to Mckenna’s March 23 interview on NPR’s Fresh Air program.