Today, The Writing Well is celebrating Earth Day a few days late with this insightful interview with Atlanta urban designer Ryan Gravel, author of Where We Want to Live: Reclaiming Infrastructure for a New Generation of Cities, a book that will inspire anyone who has grown up in the sprawl of America’s suburban areas where communities were designed around cars instead of people.

Today, The Writing Well is celebrating Earth Day a few days late with this insightful interview with Atlanta urban designer Ryan Gravel, author of Where We Want to Live: Reclaiming Infrastructure for a New Generation of Cities, a book that will inspire anyone who has grown up in the sprawl of America’s suburban areas where communities were designed around cars instead of people.

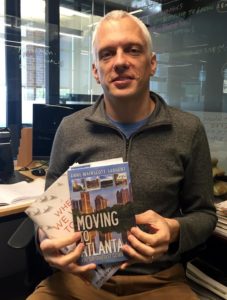

I first met Ryan while researching my own book, Moving to Atlanta: The Un-Tourist Guide. I couldn’t write about living in Atlanta without quoting the “Atlanta Beltline guy,” as he’s known around town. The Beltline today is a $4 billion infrastructure project that will add 40% to the city’s green space by converting Atlanta’s abandoned 22-mile-long freight rail corridor into a transit greenway. It’s also, as I was to learn while researching Atlanta’s many intown neighborhoods, a cultural phenomenon that is redefining the fabric of the city, bringing people and institutions together and fueling economic growth.

“The Beltline has its own culture,” Eric Champlin of AtlantaTrails.com said, and his enthusiasm for the Beltline was echoed by dozens of other residents I interviewed. For Ryan, it was his graduate thesis while an architecture student at Georgia Tech, and his vision of what he would love for Atlanta to be, inspired by what he’d seen firsthand after living for a year in Paris.

“His book is part memoir, partly an argument about what’s wrong with suburban sprawl and partly an argument about how infrastructure shapes our society and how – from roads to rivers – it can be thoughtfully repurposed,” writes Alex Bozikovic in his March 18th review of Ryan’s book in The Globe and Mail.

I am inspired by Ryan’s passion for Atlanta, but I agree with The Globe and Mail reviewer that Where We Want to Live has a much broader perspective, with examples of what other cities here and abroad can do to make their communities more livable, more equitable, and more sustainable.

In my book, he credits the people for Atlanta for making the Beltline happen, saying, “The only reason we are doing this is because the people of Atlanta fell in love with a vision for their future.” He predicts Atlanta will be a very different place in 20 years — “redefined.”

Our books’ were published a month apart, and we exchanged signed copies last month at his office in Ponce City Market, a short walk from the Beltline’s Northside Trail. During our meeting, I asked him about his writing journey, including his goals for Where We Want to Live and what he’d like to be doing in five years. Here’s what he said.

Q. Why did you write Where We Want to Live?

Ryan: There were several things I wanted to accomplish — one, I am fascinated with the role of infrastructure. It is the foundation of our culture, our social life, I am fascinated with that relationship. I see it as an under-the-radar kind of tool for social and cultural change, which is exciting. The other thing is I know the reason it [the Beltline] is happening is because the people in Atlanta fell in love with this vision for their future. They empowered it and made it. They obligated their political leadership to build it. They made it happen — people did it. But if you’re 25 today, you were barely a teenager at the time we were doing that. So you might not see the Beltline that way. I wanted people to see it that way. We’re still in the very early stages of it. Its successful implementation requires them to remain involved to maintain that sense of ownership of the project. I think that’s the only way we’re really going to be successful. It has to be done well and right and be done for everybody — it has be done in a way that fulfills the vision.

Q. Were you surprised by how residents of Atlanta have embraced the Beltline — did it become something much bigger than you thought it would ever be?

Ryan: Yes. I was just a kid [when I first envisioned and began working on getting support for the Beltline]. I understood this from a technical side and an architectural side of what it would do. It is doing that but the degree to which people have fallen in love with this thing has been just insane. It’s great. I’m in love with it because they’re in love with it.

Q. How is your book different than other books in your genre?

Ryan: I think it’s different because it’s a narrative — it’s a story. Most books about planning and cities are bulky technical books. They’re sort of case studies and best practices. They’ve got a catalog of ideas outlined that are helpful but are more technical. This really tries to tell the story of the role of infrastructure in our lives and that it matters, and that we might want to think more carefully about it. I think people could fall in love with infrastructure more broadly. If people fall in love with the places that they live in, they would be much more careful with some of the decisions we make.

Q. How has the Atlanta Beltline fueled your passion for reclaiming infrastructure? Did it happen before that?

Ryan: Our success [with the Beltline] has definitely fueled my fire. The other thing that it’s allowed me to do is travel and share our story nationally and increasingly internationally. I see that not only are people fascinated by what we are doing, but they also are doing some pretty interesting things themselves. The Beltline is part of a much larger story. Another thing I wanted to accomplish with the book is to put the Beltline in a much larger context– that this kind of change is happening everywhere. Atlanta is definitely a leader in this space, but it’s happening everywhere. This is part of a much larger cultural movement — in 30 years, we will have completely reshaped the way that we build cities.

Q. What are some other cities nationally or internationally you’ve been inspired by?

Ryan: The one we’ve had some real success with is the LA River. It started as a grassroots movement in the 1980s to reclaim this concrete channel as some kind

of life-affirming waterway. And they’ve been working at it a long time, but just within the last few months they’ve made enormous progress. The Army Corps of Engineers, which channelized the river in the 1930s, literally paved 80 percent of a 50-mile river with concrete just to approve a $1 billion restoration of one short short section of the Glendair Narrows [along the Los Angeles River], so it’s not just the physical transformation, which changes not only people’s lives, but changes the way agencies, organizations and businesses relate.

If you look at urban sprawl — it wasn’t some big conspiracy; it was millions of people over an extended period of time making the best decisions that they could for their families with a lot of unintended consequences. It also was a cultural momentum and, in the process, it fundamentally changed the way we built the world around us. For one, it created entire forms of bureaucracies and business models for new types of housing and new types of food was completely revolutionized. It was part of the cultural transformation in the 60s. People separate it out but it was very much tied together in the same way that this is the beginning of a similar cultural shift that is going to have both intended and unintended consequences.

I’m excited about what is happening — this kind of change — but we also have to be thoughtful, deliberate and intentional so that it supports everybody — that everybody gets to be a part of it.

Q. What do you want people to get out of this book at the end of the day?

Ryan: I would love for people to see the role of infrastructure in their lives. We have a lot of

conversations with the Atlanta Beltline Project around equity, affordability, environmental justice, mobility and all these things, and it’s great and it’s right and we should. I think we have those conversations around all the infrastructure that we build — all the big highway interchanges, all the things that we do — the big chunks of projects we spend money on.

You look at all the big highway projects — we are spending billions of dollars on massive interchange reconstructions and highway widening and managed lanes, and all those are only for people who drive cars. They are not for people who walk or ride trains, or ride bikes or move around in other ways. They are very limited in their impact and there is no dialogue around affordability. There is no dialogue around what it will do economically to communities. It will support some communities — it will expand economic development in some communities but it will do the opposite in others. I would like to shift the public dialogue so when we make these big public investments that we would have that dialogue. I think it would change a lot of the decisions we make.

Q. What was the most challenging aspect of writing this book?

Ryan: The book was a real discovery. I knew there was something to be discovered and I didn’t know what it was. There was a lot of figuring it out. It was my first book. I can tell when I read it that the first two-thirds of the book has been reworked — a lot of chapters shifted around. Between first pitching the book and the final format a lot of those pieces have been moved around a lot to frame this larger story. The last five chapters were not conceived until all those decisions were made. They were written much faster and read much better — they make more sense. It was a learning experience for me. I became a better writer in the process. I had a book outline but it kept changing. The transition between things and the logic had to be rewritten several times and it was painful, but I think it was the right thing to do. It made a better book. For example, the Beltline is in the middle four chapters but previously it was told more piecemeal across the book.

Q, What did you learn during the process that will help other writers? What would you advise other non-fiction writers?

Ryan: I had a good editor at a high level and she helped me edit — we cut a good 100 pages out of the book. It was really redundant — partly because I was shifting things around and saying things twice. I would advise writers to get a good editor — someone who can see your story with a broader perspective. I was so in the weeds I couldn’t. I had a couple of readers who gave me different feedback on different topics. One of them helped me with the Beltline section — I wanted to tell an honest story because I wasn’t the only part of the story.

Q. Have you been surprised by the reception to Where We Want to Live?

Ryan: I was blown away by the launch event. I didn’t know how many people were going to show up. The Carter Center had seats for 470 people, and I thought there is no way we are going to fill it up but we had people sitting on the steps, which was pretty amazing.

Q. What’s next for you? Do you have another book planned?

While I was in the middle of it I said there was no way I would write another book — it was so much more work than I ever thought it would be. But, I learned a lot and I became a better writer so I think the next book would not be so torturous. I love the idea of writing a children’s book. Obviously the key to that is finding a good illustrator. I also have an idea to create a more of a coffee table kind of image book. I have a ton of images from all these other projects around the world. It would be sort of a visual addendum to Where We Want to Live.

I also would love to do an Instagram book of other people looking at infrastructure in a similar way or targeting these projects. That would be a cool way to organize people who are into the future of city-building and graphically hold it together across a lot of different photography.

I have talked to people about doing an online show about infrastructure where we would share stories — such as the work going along the LA River and talking to people who can envision what that space might become. I think that would be a lot of fun and I think you could do it in a way that would be really interesting for an audience.

Q. What’s your ideal job in five years?

Ryan: I want to research the future of cities. I want to pitch ideas for what that means and host forums and discussions about everything from storm water to automated vehicles — that is, start a real civic dialogue around the infrastructure that we build and that it matters. One of the projects I am doing is called the Atlanta City Design for the City of Atlanta. We are figuring out how they are going to grow — to become something they want to be. The City of Atlanta is only a tenth of the regional population and they are going to more than double in size in the next 20 years so where is that population going to go? How do we protect things like the tree canopy and neighborhoods so that we become more of who we are and not less, and we still like it at the end of the day? We are just now starting this — it’s going to roll out over the course of the spring,summer and fall.

About the Author

RYAN GRAVEL is the founding principal of Sixpitch and creator of the Atlanta Beltline, the reinvention of a 22-mile circle of railroads that began as the subject of his master’s thesis. A designer, planner, and writer, he is increasingly called to speak to an international audience on topics as wide ranging as brownfield remediation, transportation, public health, affordable housing, and urban regeneration. Gravel lives with his family in Atlanta, Georgia. Visit Ryan’s author page at: https://ryangravel.com/ or follow him on Twitter @ryangravel.